The Creation of Lana Del Ray

One of the greatest songwriters of all time was essentially full of shit. On Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchel once said: “Bob is not authentic at all. He’s a plagiarist … his name and voice are fake. Everything about Bob is a deception.”

So why do we have no problem accepting Dylan’s Woody Guthrie-inspired sham? And why do we all seem to take Lana Del Rey’s reinvention as a personal insult? Talent does seem to have a lot to do with it. Or lack thereof …

When Dylan sings, he breathes an authentic air of truth over lyrical content that may not itself be entirely truthful. The guy is a master artist. But when Ms. Del Rey sings live, shit just gets awkward. If her infamous American debut performance on Saturday Night Live has taught us anything, it’s to not judge an artist based on the strength of two previously-recorded tracks.

By now we all know Lana Del Rey’s (birth name Elizabeth Grant) “real” story. She was not raised in a trailer park by hippies, she does not write most of her music, and her lips are most certainly not real (come on, nobody was buying it). The truth? Her father is an Internet millionaire, who ensured his progeny had the assistance of the best managers and producers in the business.

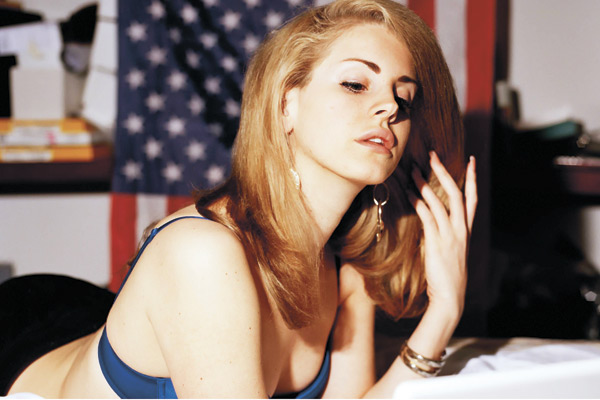

Lizzy Grant hit the New York open-mic scene in the early noughties. She failed. So Daddy stepped in and did a little makeover. Grant moved to London and changed her name to Lana Del Rey (a fusion of Hollywood glamour star Lana Turner and the midsized family car, the Ford Del Rey). And the thing about reinventions is that they sometimes work. Sex sells. And the smoky Lana Del Rey experienced a success unknown to the “honest” Lizzy Grant. Styled after Melissa George in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, Del Rey oozed old-Hollywood charm. Guys wanted her; girls wanted to be her.

In an age where Beyoncé and Adele preach staunch independence and female empowerment, Lana’s fifties-housewife act and codependent lyricism caused controversy. When Del Rey cries “You went out every night/And baby that’s alright/I told you that no matter what you did/I’d be by your side”, we can’t help but cringe.

The release of Lana’s debut recording Born To Die confirmed everyone’s suspicion that despite the artfully poignant clip for “Video Games” and the smoldering torch-song that is “Blue Jeans”, her gimmick was limited and her talent even more so. And so we find ourselves back to the initial question: Is authenticity important? If the artist makes it clear that they are using an alter-ego to try out a new sound (see Sasha Fierce or Ziggy Stardust), or a supplementary persona to create a certain artistic aesthetic (Katy Perry’s Candy Land pinup girl or Ke$ha’s drunk glitter-queen) the audience is happy to suspend their disbelief and supports the change. But when an artist makes every effort to pull the wool over the public’s eyes and manufacture an authenticity, we’re not interested in their spoon-fed bullshit.

If we found out that Biggie never sold drugs, or Jay-Z came from wealth, we wouldn’t take them seriously. Genuine tales of hardship and poverty are what make the two hip-hop heavyweights so intriguing. Same goes for Lana Del Rey. When we discovered her “authenticity” was just another aspect of her career that was constructed by a multinational corporate label, we lost interest.

The reason we are so angered by Lana Del Rey’s deception is that we so wanted to believe such an artist could exist: Aesthetically perfect and soulfully sincere. So easily were we won over by her charm that we didn’t even consider the fact that she was too good to be true. We were fooled.

– Lukas Clark-Memler