Student Soldiers

Private Edward Stace is doing fourth-year Medicine this year, and hopes to make his medical skills useful in the army someday. Edward completed his basic training last year, and his officer’s training at the start of this year.Private Murray Cadzow has just completed a Bachelor of Biomedical Science, and is keen to find a practical application for his health-related degree. He is training to become a medic, and returned from Basic Training only two weeks ago. BASIC TRAININGBasic Training for the Territorials is a seven-week-long stint on the Waiouru base (North Island). For the regular forces, training lasts 16 weeks. During this time, trainees live, breath, and eat 'army'. The 120 recruits sleep in two large barrack buildings that are broken into four wings based on the main training unit, the 30-person 'platoon.' Each platoon is broken into 'sections' of around ten people. The recruits are generally aged from 18 to 40, with the bulk of them, says Cadzow, around 18 or 19 years old.

The training includes three modules that all involve teaching, practical exercises (e.g. weapons training), and outdoor excursions, designed to endow the meek new recruits with all the necessary skills of warfare. Murray Cadzow explains that they spent a day or so on each type of weapons system, first learning its characteristics and technicalities, then doing a safety test, then practicing on the field. This included a lot of time spent with the Steyr (rifle), and also some training to use a LSWC9 (machine gun), high explosive grenades, grenade launchers, and M72s (anti-armour gear). “We also did all kinds of lectures. The theory of navigation in the bush, Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC), and other things like that. You'd learn the theory of how something would be, then you'd have to go practice it.”

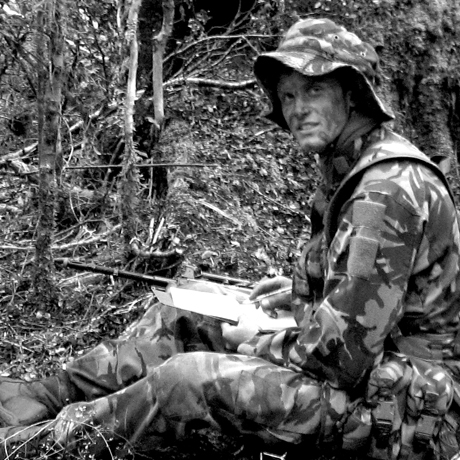

The wilderness excursions included a three-day trip to begin with, then a five-day one, and finally a ten-day outing which included training and sleeping out in both open and closed country, and an urban environment – a special army range built from old state houses. Cadzow explains that at this point in training, the groups were broken down even further: “Within a section you have assigned roles, like scouts, rifle team, gun team. They try to rotate you round, but the gunner positions were chosen based upon your training for the machine gun. For our section we had a speed competition – who could do it the fastest with the most accuracy, and confidence in the system.”

One thing that was very apparent is the incredible discipline demanded of all recruits. When asked how the army experience had changed him, Private Stace says: “I'm a lot more self-disciplined now – I guess that's a good thing!” Cadzow narrates the trials and tribulations of barrack inspection: “There was a specific way they wanted things done, like how the socks had to end up looking, and we had to find out how to roll them, and manage to get them to look like that. And other little things, like your military and civilian clothes were separated, and they faced in. The biggest thing they were going for was uniformity – originally just within the room, but when we had our platoon commander, or an officer did a barrack inspection, they'd say 'we want all the rooms completely uniform' – which was definitely a challenge.” BROTHERS IN ARMSDuring training you sleep, eat, and train with your section. Private Cadzow says, “You get to know your section really well. While you are there, your section is like your family – my section, we bonded really well.” Private Edward Stace agrees: “You grow some really strong friendships out of that sort of situation together – when you go through the kind of stuff together, you just get on with people.”In Cadzow's whole intake (around 120 people), there were only around six women by the end of the final module. Karla, one of his fellow recruits, says, “I was respected! Not given any preferential treatment overall. The guys in my section were lovely and treated me very well.” Cadzow agrees that gender doesn’t matter. “You didn't make the distinction between male and female, you are just 'recruits.' There's no real distinguishing factors. Like race – that just doesn't come into play. One of the officers said, 'we don't have races in the army – it doesn't matter if your a Pakeha or a Maori or a Pacific Islander. In the army you are just green.'” 'Comradeship' is a key focus of army life. Cadzow says, “Once you are in, everything is about teamwork. You don't do things as an individual anymore.” This is undoubtedly one of the most impacting parts of the army experience. He continues to explain that “Before I went I was pretty convinced that regardless of any situation, I'd never shoot another human being. But I suppose just being given those scenarios that could happen, and just the loyalty and comradeship (one of the values we are taught), that influences you quite a bit.”A little disappointingly, neither Stace or Cadzow reported any weird initiation rites or hazing involved in their training – in fact, their initiation into the army was a formal affair. They were formally welcomed onto the Waiouru marae and initiated into Ngati Tumatauenga (the Tribe of the War God). Private Cadzow says that this was an important element of training: “It adds a unifying culture. It helps just reinforce that everyone is the same level, whatever gender, race, age. Everyone is part of it.” They then made a pledge, and were officially 'in’.THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE MEMORABLEStace describes himself as “a bit of an outdoors-man” and his favourite part of training was “just getting out there, doing all the physical stuff. I guess I saw it as a good opportunity to thrash around the bush for a bit.” He says that the most challenging parts were those that pushed his limits physically, but that these were also the most rewarding.Cadzow's favourite memory is of the morning where they did a mock-assault on the urban range. He narrates it with gusto: “We set up a fire support team on the hill, and came down, formed up at the back of the range, and then at a specific time two teams rushed forward and took a building, and went through and cleared it of the enemy.” He stops to explain that some of the regular forces and support staff would come out and 'play enemy' for the day. He goes on: “We had Alpha and Bravo teams, which was half your section. You had two sections taking two houses, and you had another team up on the hill giving them fire protection. Our team was taking the first house, and so once we had taken that we were to give support to the second house, while that was being assaulted. Then we had to get out of that house, and run across to the next house – it was just good fun!”However, Cadzow also speaks seriously about two things that really struck him, “In one of the lectures, one of the sergeants said 'We are in the business of killing. There's really no other way to put it.' Having it put that bluntly hit quite a few people, I think – that sudden realisation. But then another staff sergeant, in a different lecture, said the New Zealand Army isn't 'peace-makers', we are 'peace-keepers.'” This echoes the line most commonly spouted about the New Zealand military: their role in peace-keeping and humanitarian aid, which does seem to have won the New Zealand forces significant international respect.DUNEDIN BATTALIONThe infantry battalion for Otago and Southland is known as '40South.' There are over 100 people enlisted in it, including Edward Stace. Murray Cadzow is part of 3HSC (Third Health Support Company), which comprises around 20 medics from the Otago-Southland area. 40South and 3HSC have offices in the same place, and sometimes join one another for training.After basic training, the Territorials are required to keep up their skills by fulfilling the equivalent of 20 days’ training per year. In Dunedin, training sessions run for three hours every Wednesday night, at Kensington Army Hall, as well as on the occasional weekend, and there is also involvement in parades and similar. No sessions are compulsory, as long as they fill their 20 days’ worth. Stace, however, has rarely missed a Wednesday night, and Cadzow too seems keen to get back into the Army ways, having been home from Basic Training for barely two weeks. Stace says the training “reinforces and builds on existing skills from Basic Training, sometimes taking them a bit further.”Full-time army recruits, after they've done basic training, are most likely to be assigned to a particular New Zealand base. Private Stace has talked to a few army doctors who seemed to think it was “Pretty sweet – working 8am till 4pm, getting paid to go to the gym!” although he imagines it is a lot more intense as a regular soldier. The trainees do get paid for their time and training at Waiouru, and for any involvement in parades, and for deployments. But they are adamant that “You don't really do the job for the money – you do it because you like it. “NZ SOLDIERS OVERSEASNew Zealand soldiers get around. There are currently 625 New Zealand Defense Force personnel deployed on 14 peacekeeping operations, UN missions, and defense exercises in ten different countries. Territorial troops would be sent over to attach themselves to an existing Unit, and go under a regular force contract. The length of the deployment depends on the location – for example, the Solomon Islands is usually a six-month deployment, with two months’ pre-deployment training. East Timor, or Afghanistan, can be around twelve months.Stace is very keen to head overseas on deployment. He is hoping to be able to combine it with his three-month medical elective through the University (required of all sixth-year Med Students). Cadzow says deployments are indeed “tempting, but the hardest part is choosing between time with family and friends, and a really cool opportunity.” He said that a lot of the younger people in his training group were keen on deployments, while those with families were generally less so. But the Territorial Forces facilitate a good balance: “it gives you that option to experience army life, without having to give up civilian life.” However, deployment opportunities for territorial troops are becoming scarcer. The recession caused a jump in enlistments, and now New Zealand's regular (full-time) force is almost fully manned. However, with the centenary of World War One fast approaching, there should be plenty of opportunities for the Territorials to parade around in uniform, and fly the country’s colours.According to Cadzow's officers at Waiouru (most of whom were Territorials who had been on multiple deployments) the Territorial Force brings something special to a situation. Cadzow explains that this is because “you've got your army training, but when you go on a deployment you also have within your group some builders, or teachers, or nurses. That's a strength of the Territorials. Also because we live with civilians, we are more used to talking to people, chatting, whereas with the regular force they are army 24/7.”STUDYING WHILE SERVING“Because so many of us are students,” explains Stace, “they're usually really good about working with our timetable and everything.” He explains that they willingly rescheduled a whole weapons training weekend recently, after realising it was in the middle of exams. Nevertheless, juggling University and the Territorials can be challenging. In fact, Stace missed the full first month of study this year to do his officer training in the North Island. He says the University was 'pretty good' about letting him miss the time, but he still has a lot to catch up on. Overall, he says, “mixing army with uni is pretty easy and enjoyable.” Both Stace and Cadzow were standing tall in their ceremonial dress uniforms at the ANZAC Day Dawn Service yesterday.