The New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations (NZUSA) has released its 2014 Income and Expenditure Survey, which shows that students are in a worse position financially than when the last survey was done in 2010.

The survey found that housing costs across New Zealand have increased between $5 and $10 per week over the last four years. These costs, and other costs of living, are rising faster than the rate of inflation.

Housing support for students has been capped at $40 per week since 2001. On the other hand, the accommodation supplement for low-income New Zealanders who are not students is up to $145.

“This means there is no immediate financial incentive to move from a benefit to study, or from a low-paid job into a qualification that could potentially move someone out of poverty in the long term,” the report argues. “Instead, potential students face the immediate impact of losing up to $105 per week in their available funds.”

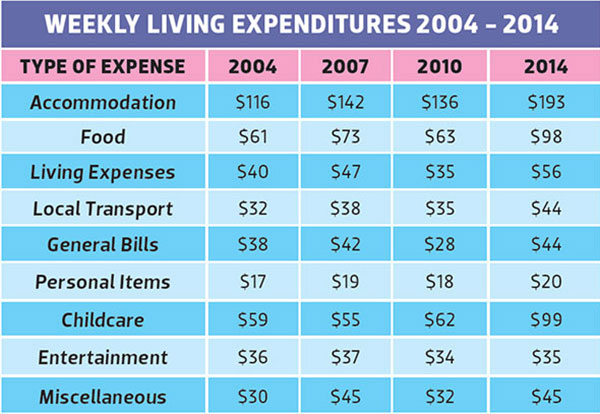

Nationwide, the average cost of accommodation has risen from $116 in 2004 to $193 in 2014. In Dunedin, housing costs have generally sat below the national average. By 2015, however, 66 percent of student income was going towards rent alone. This has jumped from 50 percent in 2003. These figures exclude students living in halls, who pay an average of $359.37 per week.

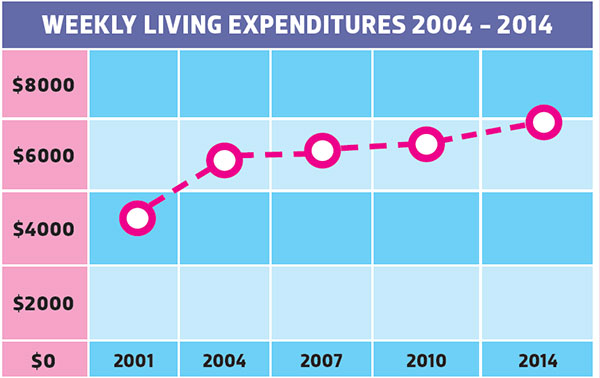

In 2010, the average university fees for students were $6246. In 2014, this increased $808 to $7054. Between 2006 and 2015, non-tuition compulsory fees increased by 29 percent. The survey also found that of students not continuing their studies, 20 percent identified the cost of study as one of the reasons. “Cost is the leading cause for leaving study behind finishing their qualification or finding employment.”

The survey showed that 90 percent of students are now in at least one form of debt, and two thirds have two or more forms of debt. In 2014, 28 percent of students were in credit card debt, a 10 percent increase from 2010.

Credit card debt and loan shark use have been found to be “on the rise” as students “try to bridge the gap between rising living costs and declining state and parental support”.

Due to reduced government support, and parental support often being unavailable, there has been “a sharp increase in student working hours”. Students now work an average of 14 hours per week, which is up from 12 hours per week four years ago.

As a result of the financial stress they are under, students’ mental health is declining. From 2009 to 2014, counselling sessions for students rose by a quarter. The report attributes this to “stress and anxiety associated with the demands from study and paid work, future employment prospects, debt and immediate financial strain”.

Of those surveyed, 56 percent said financial stress affects their study, and 66 percent worry about what they will owe once they have completed study. Those in lower socio-economic groups were found to be more stressed about their finances.

Almost half of students, 44 percent, reported that they do not have the income “to meet their basic needs”. For students in their final year, one in six were “living in significant financial stress”. This situation has worsened since 2012.

Dr Anne-Marie Brady, a professor of political science at the University of Canterbury, said: “Students are under massive financial pressure and more students are having documented cases of depression and anxiety, which is having a serious impact on their studies.”

“Many students tell me they are exhausted from their paid jobs and they cut classes to recover, miss assignments, or do not fully participate in class,” said Brady in a press release.

The survey estimates that students of today are likely to still be carrying their loan debt in their late forties. Of those surveyed, 36 percent said their loan debt is likely to affect their decision to have children, 70 percent said it will affect their ability to buy a house, and 65 percent said it would have a significant impact on whether or not they would undertake more study.

Just over one fifth of those surveyed said they will not have children until they are debt free, and another 20 percent said their loans will mean they wait longer before having children.

NZUSA President Rory McCourt said: “What this research shows is that toxic student debt is removing choices for New Zealand families. They’re delaying, deferring and deserting starting a family because of mounting debt.”

McCourt argues that the 12 percent repayment rate, which applies to every dollar earned above $19,084 per annum (or $367 per week), is “punishing for graduates and [forces] them to make decisions like delaying starting a family”.

“Our repayment threshold was originally set to ensure the poorest New Zealanders didn’t have impossible repayment obligations. By not adjusting it, we’ve increased the effective marginal tax rate for minimum wage workers to above that of the vice-chancellor and the prime minister. That is deeply wrong.”

NZUSA argues that a progressive repayment scheme, like that of Australia, would ensure New Zealanders could afford to pay their loans off at a fair rate. “In Australia graduates don’t pay a cent until they earn $54,126, and even then it’s only 4 per cent of their income. From there it goes up 0.5 per cent for every additional $6,000 earned. The top rate of 8 per cent doesn’t apply until a graduate is earning over $100,520.”

The report recommends that the course related costs loan cap, which has been frozen since 1993, be lifted to $10,000 for first-year students and $3,000 for other students. The report also makes a number of other recommendations, including that the government restore postgraduate allowances; introduce a universal housing grant in cities where rent is taking up over 70 percent of student income; increase funding for universities and polytechnics; restore allowances for over-40s; change the repayment rate and replace it with an Australian-style system; lift the parental income threshold; and introduce a $10,000 scholarship for students who are the first in their family to participate in degree-level tertiary education.